Author: Grace Shackman

What was a star architect thinking?

When I worked at the Chelsea Standard in the 1980s, I often covered events at Chelsea High School. It was not a single building, but a campus of one-story structures that students scurried between in all types of weather. I was told it was designed by a California architect who didn’t understand Michigan winters.

Imagine my surprise to learn, years later, that it was actually the work of Minoru Yamasaki, the famous Modern architect who went on to design the World Trade Center. Born in Seattle, Yamasaki moved to Detroit in 1945, so by the time he designed the school in 1956, he had been through eleven Michigan winters.

But Yamasaki evidently wasn’t thinking about winter. In a 1957 interview with Architectural Forum, he explained: “We hit upon the idea that if the buildings could each express their individual character that we might be able to depict the quality of a small town. The auditroium, gym, homemaking area would symbolically and literally be the town center.”

Chelsea High School

Yamasaki was hardly the first architect to ignore practical problems. A janitor once broke a leg tending an elevated planter at Alden Dow’s Ann ARbor library. Frank Lloyd Wright’s eccentricities – leaking roofs, tiny kitchens – are well know. But Chelsea needed a new school – the high school population, then fewer than 400 students, was predicted to double in ten years.

Local architect Art Lindauer encouraged an innovative design. “I went to the school board and said, ‘Every school looks like each other,'” recalls Lindauer, the father of Chelsea mayor Jason Lindauer. “‘Why don’t you try an architect with a different approach?'” Asked for suggestions, he mentioned Yamasaki, who at the time was activiely pursuing school work. After interviewing a dozen architects, a citizen’s committee recommended hiring Yamaski, Leinweber, and Associates.

Peter Flintoff, whose father, Howard Flintoff, was secretary of the school board, recalls hearing that they felt lucky to get Yamasaki. Alyce Riemenschneider remembers that her parents and their friends were also excited to have someone so famous design their school.

Chelsea High School

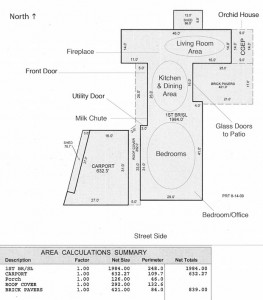

People raised questions about the campus layout, but according to the Standard, school board members argued that the design would “provide the best building program at the most economical cost.” Outside walkways would to-ceiling windows [it] was much nicer than the traditional string of hallway lockers,” recalls Carol Cameron Lauhon, who also graduated in 1961. Covered walkways with brightly colored bubbles at building entrances served to unify the campus and afford some shelter as students passed between classes.

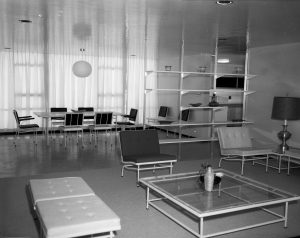

The main building, which Yamasaki called the “Town Center,” contained the cafeteria, library, gym, and auditorium. Circling the auditorium were six classrooms used for English and social sciences. A Central atrium was open to the sky and filled with planst and bushes. “For the prom, the junior class would decorate the atrium with flowers and green plastic truf and furnish it with a wooden bridge over a small pond. Couples posed on the bridge for their prom photos. Very romantic!” recalls Lauhon.

June Winans, who taught earth science and geology, shared the science building with biology, chemistry, and physics teachers. Shop classes, the Standard explained, also had their own building so that “noises made by operating equipment or hammering and sawing will not disturb other classes.”

Chelsea High School

The home economics and art building had a pitched roof to look more like a house. Riemenschneider recalls that the desks converted into cutting tables and that sewing machines were hidden in veneer cabinets. The kitchen had the newest stoves and refrigerators and an island, a novelty at the time. After preparing a meal, the students moved into a dining room and a living room.

At an open house, the Standard reported, “most people were impressed not only with the beautiful appearance of the new campus type high school but also with its very evident functional features.”

The students who made the transition still have fond memories of Yamaski’s school. “The exterior walkways between buildings felt less confining than the old school’s intererior hallways and multiple stairwells, some of them narrow and windowless,” says Lauhon.

“I was happy to walk outside,” says Brown, adding: “The teachers aid it woke the students up.”

“The breath of fresh air did them good,” says Bill Chandler, the school’s work-study coordinator. Sam Vogel, social studies teacher and later assistant principal, recalls that “the covered walkways developed leaks, but, unless it was pouring, it wasn’t a problem.”

Parents were less thrilled. Some thought it was ridiculous that their children had to go outside. One recalls her daughter tell her, “mom, we don’t need decent clothes to go to school. We just need a good coat.”

As enrollment grew, an auto mechanics garage was added, and a new bulding facing Washington for social studies. The cafeteria was enlarged by moving the library into another building.

But when the locker room got overcrowded and rowdy-the staff dubbed it “God’s Little Acre” – there was no way to expand it. Eventually the lockers were movied into the “town center,” but “then the halls were too crowded,” Vogel recalls. The atrium also became a problem, with maintenance issues and heat loss through the single-pane glass the surrounded it.

Yamasaki’s futuristic vision never caught on: the present Chelsea High, built in 1998, is again a single building. His campus, however, is still in use – its buildings now house the Chelsea Senior Center, school board offices, Chelsea Community Education and Recreation, and Chelsea Early Education. The roofs and bubble entrances are gone, the original large windows have been replaced by smaller ones, and the atrium has been filled in to create a windowless meeting room.

But students who went there still have fond memories of their school. “It seems to me that the Yamasaki design was a new way of imagining spaces for student life,” says Lauhon. “The school was a pleasant place to be. My sense is that this is what Yamasaki had in mind.”

Copyright

Copyright Protected

Rights Held By

Grace Shackman

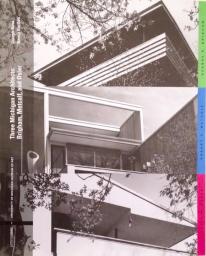

Three Michigan Architects: Brigham, Metcalf, and Osler

Three Michigan Architects: Brigham, Metcalf, and Osler