Two articles about Modern Architecture posted in the New York Times

A recent interesting article by John Dorman in the New York Times explores Saarinen’s Michigan roots.

Another NYT article, by Steven Kurutz, explains the lasting allure of MCM.

A recent interesting article by John Dorman in the New York Times explores Saarinen’s Michigan roots.

Another NYT article, by Steven Kurutz, explains the lasting allure of MCM.

Time: 1:00-3:00 p.m.

When: Saturday, September 9th, 2017

Cost: $30/person, registration required

Detroit’s Mies van der Rohe Historic District in Lafayette Park includes 186 cooperatively owned Town House and Court House units, three apartment towers, an elementary school, a retail district, and a 13-acre park known as the Lafayette Plaisance.

The neighborhood has been hailed as “one of the most spatially successful and socially significant statements in urban renewal” and as a “prototype for future urban development predicated on human values.” The site contains the largest collection of buildings by the architect Mies van der Rohe in the world, as well as the only group of row houses built to his specifications.

The tour will be conducted by Christian Unverzagt and Neil McEachern, both long-time residents of Lafayette Park. Unverzagt is an Assistant Professor of Practice in Architecture at the University of Michigan’s Taubman College. McEachern, now retired, is a former Detroit Public Schools principal.

Space is limited (only 12 tickets available), REGISTER HERE

LOGISTICS: Transportation is on your own. We will meet at the Mies van der Rohe Plaza in the Shops at Lafayette Park at 12:45 p.m. Parking is available in the shops (off Lafayette). Alternatively, public parking is available on Joliet Place and Nicolet Place (off Rivard) and the plaza may be approached from the north by walking through the Plaisance.

Below are pictures of a courtyard unit at 1320 Nicolet Pl. that is currently for sale.

On Thursday, August 17, at 6:30 P. M., Grace Shackman will lead a walking tour of Highland Road and Regent Drive. The lots on both streets were sold with the caveat that the homes be architect-designed. Architects represented include George Brigham, David Osler, Robert Metcalf, and Aldon Dow.

Tickets are $10 and can be purchased here. The tour will be limited to 20 people. Meet at the corner of Regent Drive and Highland Road, which is north of Geddes Road near the Arboretum.

Author: Grace Shackman

Even Frank Lloyd Wright approved.

Most church groups that need to relocate either buy a church building abandoned by another congregation or build a new church. But in 1946, when the Ann Arbor Unitarian Universalists left their handsome stone church at the corner of State and Huron, they moved to a house on Washtenaw.

According to the church’s current minister, Ken Phifer, using houses is not uncommon among Unitarian congregations; he could name five other examples immediately. “The Unitarians don’t worry about following any architectural standard,” he says. “Every building and every community is different.” He links this to the Unitarian belief that “individuals follow their own path.”

The Unitarians bought the house at 1917 Washtenaw from Dr. Dean Myers, a prominent eye, ear, nose, and throat specialist. Built in 1917 (by coincidence, the year matches its address on Washtenaw), the Swiss chalet-style house was one of the most elegant on a street of distinctive homes. It was well built of sturdy fieldstone and was the pride of its builders, Weinberg and Kurtz. (For years, a picture of the house was featured on the construction firm’s checks.)

The front entry area was flanked by a formal living room on the west and a library and dining room on the east. Sun rooms on each side were entered through French doors. Next to the dining room was the butler’s pantry and beyond that the kitchen and cook’s pantry. The bedrooms on the second floor had adjacent sleeping porches over the sun rooms. On the third floor were luxurious guest quarters and a maid’s apartment with sitting room and bathroom. In the basement, besides the usual storerooms and laundry room, there was a billiard room with wooden pillars and a fireplace.

Myers, who was widowed when the house was built, moved in with his daughter, Dorothy, and his mother-in-law, Mrs. Owens. He was then forty-three years old and at the peak of his career as an innovative eye surgeon. He was also active in community affairs, serving on city council and the school board and as chair of the county Democratic party. An avid golfer, Myers helped lay out the first nine holes of the Barton Hills golf course and was the first player to make a hole-in-one there.

For the first six years in the house, Myers got by with day help, but in 1923, when he married Eleanor Sheldon, the housekeeper at Betsy Barbour, he decided it would be better to have a live-in maid. On the recommendation of friends, he sponsored a seventeen-year-old immigrant girl from Swabia in southern Germany. Carolina Schumacher (she married Gottlob Schumacher in 1930) cooked, washed, and ironed for the family.

Mrs. Schumacher still remembers her first day. She had to enter through the back door because Washtenaw was being paved and was covered with straw. She remembers Dr. Myers as “nice looking, tall and bald headed, always smiling.” (He used to say, she recalls, that “you can’t have brains and hair too.”)

The house was grandly furnished, with oriental rugs throughout and a grand piano in the living room. Before dinner, Myers liked to sing, accompanied by Dorothy at the piano. The Myerses entertained frequently, often other well-known local doctors, like Albert Furstenberg and R. Bishop Canfield, and sometimes visiting out-of-town doctors.

Mrs. Schumacher left the Myerses’ employ when she and her husband started the Old German restaurant. After Mrs. Owens’s death and Dorothy’s decision to move in with a friend, Dr. and Mrs. Myers stayed in the big house until 1946, when they moved to Hildene Manor, the gracious Tudor-style apartment building at 2220 Washtenaw. Dr. Myers died in 1955 and his wife a few years later.

The Ann Arbor Unitarians had been in their church at State and Huron since 1883, and the decision to move was a difficult one. Parishioners–including the children of Jabez Sunderland, the minister under whom the church had been built–realized the historic value of the old building, both architecturally and as a repository of memories. But it had deteriorated, inside and out, and the costs of repair far exceeded the church’s resources. The Depression and then World War II had depleted the membership; when Ed Redman took over the ministry in 1943, there were sixteen contributing member families.

Don Campbell, then the church treasurer, says that the old church “was like a barn–cold, hard to heat, dirty.” Services were held in the library, which was easier to heat, because it was rare for more than thirty-five people to show up.

Ironically, it was Redman’s success in bringing the membership back up that sounded the death knell for the old church. He attracted young families, many with children, and soon the church could not provide the needed Sunday School space, even spreading out to the parsonage next door on State Street. When, in 1945, the Grace Bible Church offered the Unitarians $65,000 for the old building, they accepted the offer and began to search in earnest for a new home. The following year they bought the Myers house for $46,000.

On February 3, 1946, Redman gave his last sermon in the old church. It was entitled “Sixty-Four Glorious Years.” After a few months in Lane Hall, he delivered the premiere sermon in the Myerses’ former living room, calling it “Birth of a New Age.” The house took on an entirely new identity. Church social events were held in the old dining room, while the Sunday School met in the second- and third-floor bedrooms.

The Redmans had planned to live in a parsonage on Packard, but they found the house too small (Redman and his wife, Annette, had five children) and preferred to live closer to the action. A parsonage addition was built at the back of the house, one floor in 1948 and a second in 1955. By the fall of 1951, it was obvious that the church was outgrowing its house. Redman, in his recollections published by the church in 1988, wrote, “The worship services could not be contained in the original living room space of the chalet. John Shepard had installed storm windows in the side porch, and it was quite fully occupied except in the most severe weather. The entry hallway provided additional seating space extending all the way into the original sun room. And the main stairway was also often occupied!”

The church began collecting money for an addition, receiving pledges for $40,000. George Brigham, a prominent architect on the U-M faculty and a church member, was hired to design the addition with an auditorium upstairs and a social hall and kitchen downstairs.

According to Redman’s memoir, Brigham’s charge was “safeguarding the architectural integrity of the existing chalet and the design of additions, which would pick up on the theme of the chalet to create a total facility blending in a unified way with its landscape.” Redman continues proudly: “That the goal was substantially achieved by Professor Brigham was attested when the renowned Unitarian architectural master Frank Lloyd Wright expressed one of his rare approvals by exclaiming, ‘That’s good!’ ”

Today the church stands as completed in 1956, except for a change in the roof line to make the building easier to heat. The section that was the Myers house is used for offices: dining room for main office, master bedroom for minister’s study, Mrs. Owens’s bedroom for the religious education director’s office. The sun room off the living room is the library. The National Organization for Women rents an office on the second floor, and the old parsonage is often rented during the week by preschool groups. The carriage house where the Schumachers lived is now home to a Salvadoran refugee family sponsored by the church.

The Unitarian Universalist church continues to thrive in the space, with a membership of 416, not counting children. Phifer, who fell in love with the building the moment he saw it, says, “I never heard anyone say anything but praiseworthy about it.”

Grace Bible eventually outgrew the old church at State and Huron, moving to an ambitious new complex on South Maple Road. The building sat vacant and deteriorating for several years until it was finally restored as the offices of Hobbs and Black architects. It was an ideal solution: Hobbs and Black got a showpiece office, and the building a proud, well-heeled tenant. “It’s beautiful, but it cost an arm and a leg,” Don Campbell says of the restoration. “The church didn’t have that kind of money.”

[Photo caption from original print edition]: The Unitarians’ additions have been so subtly done that today’s expansive church (above) looks surprisingly unaltered from its days as a private home (right).

Author: Grace Shackman

The stately and prestigious Women’s City Club started as a simple farmhouse.

In its 100-plus years, 1830 Washtenaw has changed in harmony with the street it faces. Built when Washtenaw was a dirt country road, it was first a simple, boxy farmhouse. When Washtenaw became a fashionable address, the house was ingeniously transformed into an imposing home for a wealthy physician. As the Women’s City Club since 1951, it has continued to evolve, expanding physically and adapting socially as it moves to encompass the needs of career women as well as club women. It provides meeting space for seventeen member clubs and 900 individual members, to whom its dining room, lounges, and library are an ideal place to hang out, entertain guests, or, in the case of the increasing number of professional women members, meet with clients.

The house was built by Evart Scott, who moved to Ann Arbor from Ohio in 1868 to attend the U-M. Scott completed only two years of college, but stayed in town to become a successful businessman, civic activist, and farmer. He was president of the Ann Arbor Agricultural Co., which ran a mill at Argo dam, and a member of the school board, the public works board, and the board of Forest Hills Cemetery.

The house was built by Evart Scott, who moved to Ann Arbor from Ohio in 1868 to attend the U-M. Scott completed only two years of college, but stayed in town to become a successful businessman, civic activist, and farmer. He was president of the Ann Arbor Agricultural Co., which ran a mill at Argo dam, and a member of the school board, the public works board, and the board of Forest Hills Cemetery.

Scott moved into the house on Washtenaw in 1886, a few years after starting an orchard and nursery on what was then a thirty-acre plot just outside the city limits. He planted elm trees along his 1,000-foot Washtenaw frontage (from present-day Ferdon all the way to Austin) and named it “Elm Fruit Farm.”

In 1915, after the city had annexed the area, Scott sold the bulk of his farmland to Charles Spooner. Spooner subdivided it into building lots and, in collaboration with architect Fiske Kimball, built the elegant homes that still grace the neighborhood. Reminders of the land’s earlier owner can be found in the street names Scottwood and Austin (the name of Scott’s father, brother, and son) and in a few ancient fruit trees, most of them pear, found in the neighborhood.

Two years after selling the land, Scott moved to a smaller house at 1930 Washtenaw, on the eastern edge of his property. He sold the big house and three acres of land to Dr. R. Bishop Canfield, a professor in the medical school who was returning to town after wartime duty in the U.S. Medical Corps.

Canfield hired architect Lewis J. Boynton to turn the forty-year-old farmhouse into something more suitable for its increasingly prestigious address. Boynton succeeded in  transforming the simple box into an impressive house in the then fashionable Dutch colonial revival style. He replaced the old-fashioned wraparound porch with small extensions on each end of the house. Then he added a massive sloping roof that came down over the porches and allowed the attic windows to peek through as dormers. The finishing touch was a delicate front entrance porch with slender Ionic columns.

transforming the simple box into an impressive house in the then fashionable Dutch colonial revival style. He replaced the old-fashioned wraparound porch with small extensions on each end of the house. Then he added a massive sloping roof that came down over the porches and allowed the attic windows to peek through as dormers. The finishing touch was a delicate front entrance porch with slender Ionic columns.

Canfield was one of the nation’s leading specialists in ear, nose, and throat problems. He and his wife, Leila, a nurse from Colorado, had one child, a redheaded adopted daughter, Barbara. Alva Sink, a longtime member of the Women’s City Club, knew the Canfield family well. For three of the years that she was a student at the U-M in the early 1920’s, she ran a private school on their third floor, teaching Barbara and five other children of prominent families, including Jane Burton, daughter of the U-M president. Mrs. Sink remembers the Canfield house as “beautiful,” and says that the interior “looked much as it does today.” She recalls that Mrs. Canfield’s help included a cook, maid, and yardman.

Canfield died in 1932, at age fifty-eight, when his car ran into a tree near the present site of Arborland. He was returning home after driving his wife and daughter and Dr. and Mrs. A. C. Furstenberg (he would later become dean of the medical school) to Detroit to catch a train to New York, where all but Mrs. Canfield were to sail for Europe. Mrs. Canfield hurried home as soon as she received news of her husband’s death. Unfortunately, the Furstenbergs and Barbara had already sailed. Informed by ship’s radio, they could do nothing but sail on to Gilbraltar, where they boarded a ship returning to the U.S.

Mrs. Canfield continued to live in the house until her death almost twenty years later. When the house went on the market in 1950, a group of local women were looking for a location for a women’s club. Up to then, many groups had met on campus, especially in the Women’s League, but increased enrollment at the U-M after World War II made university space harder to obtain.

By then, too, Washtenaw’s big houses weren’t quite so desirable as they’d been: few postwar families could afford servants to care for rambling buildings and grounds, and the street’s increasingly heavy traffic was a worry for children. (Washtenaw at that time was part of Route 23, which went through town.) To the chagrin of residents, some houses were being taken over by fraternities, sororities, and other institutional users like the First Unitarian Church, which had recently bought and remodeled a former home down the block.

There was opposition to the conversion of the Canfield home, but the proponents were capable, well-connected, and hardworking women. When critics said the house was not strong enough to hold the weight of large gatherings, member Elsie White had her husband, Dr. Albert White, head of engineering research at the U-M, arranged to have the house checked. Free financial advice was given by Earl Cress of Ann Arbor Trust, while the Roscoe Bonisteels, Sr. and Jr., donated legal advice.

The key hurdle of changing the residential zoning was solved after the group negotiated an agreement with the six nearest neighbors that they would tell the city council they had no objections to the club as long as there were no exits from the rear onto Norway.

After Barbara Canfield, by then married  and living in Chicago, accepted the City Club’s offer of $45,000 in January of 1951, the group went to work raising money. Margaret Towsley, secretary of the founding group, sent letters to all the women’s clubs in town asking them to join and also to encourage at least a quarter of their group to enroll as individual members. Twenty-one clubs and 600 individual members responded, and by June 20, 1951, the final papers were signed. Supplementing membership fees with fund-raising activities, the group managed to pay the entire mortgage within five years. Just six years later, architect Ralph Hammett was hired to design a modern addition to house a large dining room, auditorium, office, main lobby, and lounge.

and living in Chicago, accepted the City Club’s offer of $45,000 in January of 1951, the group went to work raising money. Margaret Towsley, secretary of the founding group, sent letters to all the women’s clubs in town asking them to join and also to encourage at least a quarter of their group to enroll as individual members. Twenty-one clubs and 600 individual members responded, and by June 20, 1951, the final papers were signed. Supplementing membership fees with fund-raising activities, the group managed to pay the entire mortgage within five years. Just six years later, architect Ralph Hammett was hired to design a modern addition to house a large dining room, auditorium, office, main lobby, and lounge.

Today, women’s clubs in many cities have lost members or completely ceased to exist due to the large number of women working outside the home. So far, the Ann Arbor club has maintained itself well. Though membership has fallen by about 200 women from its peak in 1970, the club is actively recruiting younger members with more evening programs, more events open to men, and a deferred membership payment plan for daughters of members. (The membership initiation fee is $200 and annual dues are $175.) Some of the younger members are housewives deferring careers to raise children, but many are career women – real estate agents, lawyers, and accountants. Says club archivist Ruth Whitaker, “It provides a forum for women doing volunteer work to touch base with people in the work world.” Club president Greta Smith adds, “It’s a good way to meet people if you’re new in the area.”

Most importantly, enthusiasm is still high. Elsie White describes the club as “a great blessing to the community,” while Sink says, “It’s the best thing Ann Arbor ever did for women – or rather, that they did for themselves.”

If you can grab a copy of the June edition of the Ann Arbor Observer, flip to page 47 and read Grace’s article entitled “Midcentury Mail”. Learn how Kelly MacArthur is using her graphic design skills to create unique mailboxes for midcentury modern homes in Ann Arbor.

There will be an open house on Sunday, June 11th from 11:00 AM to 1:00 PM at 3087 Overridge Road in Ann Arbor Hills. Tickets can be purchase here.

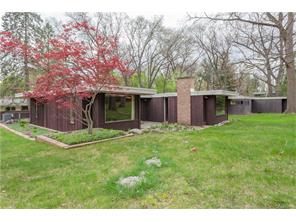

This beautiful home was designed by Edward Olencki in 1962 for the Engels and purchased by the Kleins in 1989.

Once she found herself inside this extraordinary hilltop house, Sally Klein was sure it was for her. Leaving behind their beautiful place in the country (actually Irene Olencki sold their house for them), the Kleins moved into 3087 Overridge Road in 1989. The previous owners kept the house in immaculate condition, so very little needed to be done to accommodate her family. She said that husband Tom, a mechanical engineer, took a little more time but he eventually came around to loving this Midcentury Modern masterpiece (1962) by Edward Olencki, one of three residences designed by him in Ann Arbor.

Edward Olencki came to the College of Architecture and Design at the University of Michigan in 1948, having graduated from Illinois Institute of Technology. He had worked as a draftsman and designer in the office of Mies van der Rohe in Chicago from 1943 to 1948. At Michigan he taught courses in construction materials and methods, comprehensive architectural design, and furniture design. He also ran his own architectural firm, designing homes, churches, and commercial buildings.

The Klein House on Overridge is barely visible from the street, but the ascent up the driveway instigates an Oh My Word! sense of an unfolding palace, white, somewhat austere, rising up a cliff face. The open garage leads the eye to take in the layered forms of courtyard wall, first level, second level and additional chamber farther back. And the house is sited so it’s impossible to comprehend the full scale of the house as it reaches into the surrounding ridge and trees.

Sally Klein made the comment that in the case of this house the outside is more important than the inside. She was referring to the dramatic site but once inside and having climbed the stairway to the main level, the interior dimensions convey an airy feeling of openness and light. Placed on a north south axis, three large rectangular areas accommodate sleeping quarters, living room, and kitchen dining room. On the north end a screened porch looks over a saddleback horizon into forest trees. The detailing in the house, which has remained intact (except for the removal of one bookcase to downstairs and modifications in the kitchen), employs light-toned wood surfaces and large windows. The predominately white interior with black accents adds to the serenity of these light-filled spaces.

For the walkway to the house itself, Sally traded out concrete steps for large granite stepping stones, which better complement the approach to porch area and main entrance. No description can realize how this house takes hold of the imagination. It embodies the essence of Midcentury Modern house design in its use of site, simple materials, elegant proportions and landscaped setting. This is a wonder filled house.

The longtime home of architect Robert C. Metcalf at 1052 Arlington, in Arbor Hills, is now for sale.

According to Gregory Saldana, Curator for a University of Michigan’s Taubman College of Architecture Exhibit in 2010 that that celebrated Metcalf’s work:

“In 1952 Bob and his wife Bettie began constructing their own house on two lots in Ann Arbor at Arlington Boulevard. Both held day jobs and would meet at the job site in the afternoons. They worked along side each other in all aspects of construction including shoveling, mixing mortar, laying bricks and regularly having dinner on site. “

The Metcalf’s home served as the starting point for 68 more Metcalf-designed homes in Ann Arbor, as friends, neighbors, and colleagues toured and visited, and were inspired by what they saw.

Author: Grace Shackman

Thanks to Frank Lloyd Wright, Bill and Mary Palmer raised their family in a work of art.

On a Saturday morning a little over a year ago, a group that included prominent local architect Larry Brink; Doug Kelbaugh, dean of the U-M’s Taubman College of Architecture and Urban Planning; builder Bruce Niethammer; and George Colone, a heating specialist from Hutzel Plumbing & Heating, met to discuss a failing radiant heat system beneath the concrete floor of a fifty-year-old house. If it had been just any house, the solution would have been obvious: jackhammer the concrete and replace the pipes. But on hearing that suggestion, owner Mary Palmer recalls, “I nearly fainted. It wasn’t acceptable.” The reason so many people shared her concern was that the floor in question was designed by Frank Lloyd Wright.

The group worked out a solution that would preserve the part of the radiant system that still worked, about a third of the total. Hutzel would install a new boiler and radiators to heat the rest of the house–but would hide all the new components behind couches, inside cabinets, and under beds.

“ ‘Change’ is not in the vocabulary up there,” says Bruce Niethammer, who’s worked on the house since 1974.

Larry Brink trained under Wright and has consulted on hundreds of Wright homes. “The Palmers maintained their house the best of all owners,” Brink says. “They took the best care of the house from day one.”

Larry Brink trained under Wright and has consulted on hundreds of Wright homes. “The Palmers maintained their house the best of all owners,” Brink says. “They took the best care of the house from day one.”

But while staying true to Wright and his principles, Mary and her husband, Bill, made the house their own, using it to express and enhance their interests in music, yoga, gardening, and art. “You take something, it becomes part of you, you become part of it,” explains the Palmers’ good friend Priscilla Neel, who is also an architect. “That’s what makes a building individual.”

It was quite a coup in 1950 to get the foremost architect of the century to design a house for a young couple in Ann Arbor. The Palmers had no “in” with Wright; they just asked him. But from meeting Mary Palmer fifty years later, it is clear why she would be drawn to Frank Lloyd Wright. A gracious lady with a hint of a southern accent (she grew up in North Carolina), her whole demeanor–her simple but elegant style of dress, her artistic sense, and her concern with doing things right–fit into a whole, like the perfectly integrated details of a Wright design.

Mary and Bill Palmer met as students at the U-M–Mary in music and Bill in economics. After graduation Bill was asked to stay and teach. In the early years of their marriage, the Palmers lived in an old farmhouse on Geddes, now the home of attorney Clan Crawford. The older women in the neighborhood befriended Mary. “They broke the rules about not inviting instructors to dinner parties,” she recalls. “These ladies knew gardens, literature–they were rich in what Ann Arbor had to offer.”

Elizabeth Inglis, who lived in the family estate on Highland (today the U-M’s Inglis House), was one of these remarkable women. One morning she phoned Mary to tell her that the road behind her house was being extended for building sites. Mary called Bill at work, and he came home at lunchtime. Mrs. Inglis, in gardening boots, showed them what she considered the best lot. “This is the most beautiful place in the city,” she told them. The young couple took her advice and bought both that lot and the one next to it–a total of one and a half acres of varied terrain.

Mary, a woman of wide intellectual interests, spent hours reading at the U-M’s architecture library while thinking about what kind of house to build on the site on Orchard Hills Drive. At the time she was very interested in antiques, so it might seem natural that she would have been drawn to a traditional style. But she was also very interested in Japan, one of Wright’s sources of inspiration. She had visited Japan, audited classes on Japanese art, and taken Japanese language classes.

Mary’s reading led her to Wright. The architect was then eighty-three years old but still active. Hoping to see one of his homes for herself, Mary telephoned Gregor and Elizabeth Affleck, who lived in a 1941 Wright house in Bloomfield Hills. The Afflecks responded by inviting the Palmers to dinner. Bill and Mary drove to Bloomfield Hills on a frigid February day. “We had an ‘experience,’ ” Mary recalls. “And they had as much of an experience showing it to us as we had. How it felt to be in one of Mr. Wright’s buildings opened up to me!”

On the way home Mary said to Bill, “Let’s see if we can get Mr. Wright.” Bill agreed it was worth a try. He thought that the project might appeal to Wright: Ann Arbor, despite the presence of the U-M architecture school, had no example of Wright’s work.

Mary wrote Wright a letter that concluded, “I hope you will design our house and we will not have to go to a lesser architect.” Her mother, who lived in Raleigh, North Carolina, had told her that Wright was going to be lecturing at North Carolina State, so Mary suggested in her letter that they could meet there. Wright agreed.

The Palmers attended the lecture and then gave Wright a topographic map of their property. “He opened it and looked at it,” Mary recalls. “Then he looked up, rolled it back up, and said, ‘I’ll design your house.’ It was that simple.” Not known for false modesty, Wright told them, “Wouldn’t it be wonderful for your children to grow up in one of my houses?”

Thinking back, Mary Palmer suspects Wright accepted the commission because “he saw a young couple who were really going to build–who wouldn’t back out. There was a big falloff of clients, many who went to him for designs never built.”

Some months later, the Palmers picked up the house plans at Taliesin, Wright’s home and studio in Spring Green, Wisconsin. Wright delivered the plans and left the Palmers alone to review them. The most striking detail was that the design was made up of equilateral triangles instead of the rectangles of a traditional house.

“I must say when we looked at the triangular module it was a surprise,” Mary recalls, “because we didn’t ask for it. But I had some background, because I was familiar with the Anthony house in Benton Harbor.” As he had with the Anthony house, Wright had produced a floor plan without a single conventional ninety-degree angle–every angle is either 60 or 120 degrees.

Although familiar with architectural styles, the Palmers had never seen preliminary plans and were not quite sure how to interpret them. When Wright returned to the room after about fifteen minutes, he told them to take the plans home and think about it. They showed the plans to Mary’s family in North Carolina, who also found themselves at sea. After a month or two of pondering, they got back to Wright and told him the house was too small.

Mary expected some resistance, because “the plan looked so perfect as it was,” but Wright replied that he was just trying to keep costs down for their sake. “He enlarged the house with no trouble,” she recalls. Wright made the bedrooms several modules larger, added a mud room and pantry to free up space in the kitchen, and put a study for Bill at the back of the house.

The plans, now kept at the U-M’s Bentley Historical Library, detail not only the building materials but also the design and placement of the furniture (most of it built in) and even the color scheme–Wright’s signature “Cherokee red.” For the exterior, the architect specified red tidewater cypress, sand-molded brick, and a matching perforated concrete block. Part of the roof would be flat; the sloping portion would have red cedar shingles. Although Wright was not big on basements, he included a small utility basement under the kitchen. The rest of the house would be constructed on a concrete slab finished with a red glaze coat called “colorundrum.” (Maintaining the slab’s appearance was a major goal of the recent heating repair.)

The Palmers hired Erwin Niethammer, Bruce’s uncle, to build the house. “He was one of the best builders around,” recalls local architect David Osler. Niethammer was also well suited to the job because he was not easily intimidated–“He didn’t take nonsense from anyone,” according to Osler.

Mary Palmer recalls that Niethammer was “receptive to the unusual. He looked at the plans and said he’d never seen anything like it, but thought he could build the house.” He also told her they were the most “beautiful set of plans he’d ever worked with.”

Gathering the materials was probably the biggest challenge. The cypress had to be specially ordered, the blocks specially fired. Working with Fingerle Lumber and Niethammer, the Palmers found the best craftsmen in the area to make the built-in furniture.

Bruce Niethammer was only four when the house was being built, but he still has a vivid memory of a Sunday drive his family took to the site. “We saw the house up on the hill and piles of dirt and lumber,” Niethammer recalls.

“It was an event,” recalls Priscilla Neel, who visited the site regularly during construction. So did Bob Metcalf, a U-M architecture prof and future dean. “It was a unique experience for a town to have a Frank Lloyd Wright house,” Metcalf remembers. David Osler, too, was a frequent visitor. John Howe, the head draftsman at Taliesin, came by periodically to make sure things were going all right, but so far as these sidewalk superintendents could tell, Niethammer seemed to do fine on his own.

Of course the Palmers, living just a few blocks away, also viewed the progress of the house. “When it was being constructed, we all went out to see it over and over,” recalls the Palmers’ daughter, Mary Louise Dunn, then about ten. “We saw it was going to be marvelous.”

Mary Palmer says she left most of the decisions about the house to the architect. “Mr. Wright was not autocratic–just sure of himself,” she recalls. “He would say ‘I don’t think you’d like . . . ’–and he was always right.”

The Palmers moved into the house shortly before Christmas 1952. The large triangular living area at the center of the home was ideal both for family life and for entertaining. It has windows on two of its three sides, and a pyramidal ceiling formed by three triangular sections.

The room is still arranged exactly as it was in Wright’s plans half a century ago, with a grand piano as the focal point. People sitting on the built-in couch, a parallelogram, look toward the piano and onto the grounds beyond. Between the couch and piano on the right is a large brick fireplace. On the left side of the room are the Wright-designed dining table and chairs, and tucked behind them is the kitchen, separated from the living area by specially manufactured perforated blocks.

The ceiling in the sleeping wing is much lower, as is common in Wright houses. (The architect was a short man, and some have speculated that he would have made the rooms higher had he been taller.) A more pedestrian architect might have switched to a conventional design for this less visible area, but Wright continued his triangular pattern, even designing hexagonal built-in beds in the master bedroom and children’s rooms. (Mary Palmer used to have sheets specially made but now just folds them under.) The house is situated so that the bedrooms get morning sun.

The living room’s unexpected angles and peaked ceiling, the sun pouring in the large windows, the view of the landscaped backyard–all combine to create a breathtaking experience. After almost fifty years, Mary Palmer says, she is still continually amazed by the beauty of the house.

When the Palmers first moved in, their two children, Mary Louise and Adrian, were still young, and they tried to lead as normal a family life as possible. “We used the house,” says Mary Louise Dunn. Asked whether it was hard to live there, Dunn replies, “There was always a standard of how to treat the house–higher than most, imposed by the house. There was no basement rec room, no place that wasn’t absolutely beautiful.” But, she adds, “the payoff, if we couldn’t do anything like everyone else, was that it was so special.” The semirural location (it was outside the city limits until 1999) also allowed activities that couldn’t be done in a more urban setting, such as taking Sassafras, the neighbors’ donkey, down to Nichols Arboretum to ride. When Dunn was a teenager, she had parties like other kids, rolling up the rugs and dancing to rock ’n’ roll.

After living in the house a few years, the Palmers put in a terrace off the living room. Wright had said that the terrace, which was part of his original plan, would be a good place to have weddings, and in time both Mary Louise and Adrian would be married there.

In 1964, after a visit to Japan, the Palmers built a Japanese garden house, which they used as a guest house and meditation area. By then Wright was dead, but Taliesin’s John Howe designed it in the same style as the house, complete with a three-section pyramidal ceiling. The last major change was a garden wall that Brink executed, using Wright’s design with a few necessary modifications.

Elizabeth Inglis suggested that the Palmers wait a year before starting to landscape, so that they could see what they had. Since the site was once an orchard, there were some beautiful trees on the lot, including apple trees that went back several decades. When they were ready to begin, Inglis sent her own gardener, Walter Stampfli, over with flats of pachysandra and euonymus. The garden turned into a lifetime passion for both Palmers. “It was a real collaboration between Mother and Father,” recalls Dunn. “Mother was the artistic one. She gave unstinting consideration to the whole garden, considering it from every angle.” Of her father she says, “He was a great gardener, actually planting, appreciating plants, doing cuttings, watering, fertilizing.” The garden, which even today is being further refined, follows the site’s natural contours and uses a limited palette of plant materials. Although formed with great art, it looks utterly natural.

Mr. Wright, as Mary Palmer calls him to this day, did not see the house until it was finished. She remembers his first visit: “He didn’t look at the house. He went right to the piano and sat down and played.” Asked what he played, she replies, “Something he composed extemporaneously.” Music was a shared interest for the architect and his clients: Wright once told Mary, “If you didn’t like music, you wouldn’t like my architecture.” Wright, whose father had been a music teacher before studying for the ministry, often compared his architecture to music.

Wright stayed overnight with the Palmers in 1958. Invited by the U-M architecture students to give a lecture, he agreed on the condition that he would talk only to them and not to their professors. Wright slept in one of the Palmers’ hexagonal beds and had oatmeal for breakfast.

On an earlier visit to Michigan, in 1954, when he was to lecture at the Masonic Temple in Detroit, he stayed with the Afflecks but came to the Palmers’ for dinner. Gil Ross, a U-M faculty member and the first violinist of the university-based Stanley Quartet, was a close friend of the Palmers, so they asked him if the quartet would perform for Wright. Mary recalls that they opened with a Haydn quartet. When the first movement ended, Wright stopped them, saying something was wrong. Everyone looked uncomfortable–the Stanley Quartet were first-rate musicians. Then Wright explained that their playing was fine but that their location bothered him. He walked over and helped them move their music stands and chairs between two piers leading out to the terrace, where he thought the music would sound better.

Many of the Palmers’ friends were people connected with music. “I first knew the music faculty as teachers, then as friends. It was the beginning of all our friendships,” recalls Mary. Both Palmers were active in the University Musical Society and the Ann Arbor Symphony Orchestra and often entertained musical luminaries in their house. Dunn recalls meeting such performers as Lena Horne and Frederica von Stade.

The Palmers’ yearly caroling party is also fondly remembered by those who attended. “About twenty families would sing and then eat. Mary’s was a perfect place for it because of the sensational acoustics,” recalls publisher Phil Power, whose parents, Eugene and Sadie Power, were good friends of the Palmers. Dunn recalls that at Christmastime her mother would bring out a special set of Welsh bells, spanning two octaves, to add to the music from the piano.

Mary’s interest in music segued serendipitously into another interest: yoga. Bill Palmer got to know many foreign students in college, and Mary first heard of yoga through his Indian friends. When she went to the Y to sign up for her first yoga class, she was pleasantly surprised to run into her good friend Priscilla Neel putting her name down for the same class.

Palmer and Neel’s original teacher was an American, as was her replacement. Both teachers did their best, but in retrospect, Neel says, the exercises were “by rote-more like calisthenics.” When the second teacher was leaving, she told Palmer and Neel that they should take over. The second teacher had encouraged them to read some of the yoga literature, including B. K. S. Iyengar’s Light on Yoga, which came out in 1966 with a foreword by violinist Yehudi Menuhin.

“Of all the artists who come to Ann Arbor, the one I’d really like to meet is Mr. Menuhin,” Mary Palmer told Alva Sink, whose husband, Charles, then headed the University Musical Society. Later, when Menuhin came for a concert, the Sinks invited the Palmers to a small party afterward. Mary took Iyengar’s book with her and told Menuhin that she wanted to go to India and study with the author. “Without batting an eye, he said, ‘You must go,’ ” she recalls. “He was pleased someone knew about this dimension of his life.” When Bill was on sabbatical, she traveled to India, carrying a letter of introduction from Menuhin, and met with Iyengar in Poona.

“She came back very enthusiastic,” recalls Neel. The women and a few friends began to practice yoga at the Palmers’ house. “One of us would read [Iyengar’s book] on tape. Then we’d put it on and learn the positions,” recalls Neel. In 1973 they convinced the Y to sponsor Iyengar’s first visit to the United States. “Then he came and showed us how to really do it,” Neel recalls. For the next decade, until he retired, Iyengar visited Ann Arbor regularly. After coming to Ann Arbor, he was invited to cities all around the country and attracted students to India, where Palmer and Neel helped him open a yoga institute. “Mary always entertained when Iyengar was in town,” Neel recalls. “He’d stay at her house.”

Iyengar was only one of many guests over the years, some drawn by fascination with Wright’s architecture, others by the warmth of the Palmers and their shared interests. “Mary’s an incredibly gracious hostess,” says Anne Glendon. “The house and her intellectual interests are a unified whole.”

Glendon recalls a spring party to honor Carl St. Clair, then conductor of the Ann Arbor Symphony, when “the grounds were beautiful with daffodils.” David Osler, whose wife, Connie, started the docent program at the U-M Museum of Art, remembers a gathering at the Palmers’ in honor of Marshall Wu, the curator of Asian art. “Magic,” says Osler. “It was a warm fall evening. The moon was out. Everything was waxed and polished.” One party that stands out in Mary’s mind is a dinner she gave for Yehudi Menuhin. “He liked to sit on the floor, so we had tables sitting on the floor with white tablecloths.”

Different visitors respond to different aspects of the house. Architect Ralph Youngren, impressed to find all the original furniture still in place, was intrigued by “the odd-shaped drawers and dressers” and by the Palmers’ attention to detail, down to the special red gravel they ordered for the driveway. Ann Arbor Building Department head Larry Pickel was struck by how the hexagonal shape of the beds made it impossible to put pillows next to each other.

“I was fascinated by being in a Frank Lloyd Wright house,” says retired U-M surgeon Herb Sloan. “I’d been in Wright houses that were museums, but not one where someone lived.” Judy Dow Rumelhart, who used to live across the street, remembers how she “adored going out in the teahouse. It’s a romantic house–another world.” Mary Louise Dunn says that even her teenage friends responded to the architecture: “You couldn’t be human and not recognize it’s unique.”

Although the Palmers were generous in sharing their house, Bill and Mary also guarded their privacy. They opened their home to the general public on only two occasions. In the 1980s they allowed it to be shown on the Women’s City Club Tour, helping to make that year’s tour the most lucrative ever. A few years ago Mary opened her house for a UMS fund-raiser that sold out instantly.

Bill Palmer died in November 2000. Mary is still enjoying the house. It’s Wright’s only house in Ann Arbor–unless one counts a house on Holden Drive that was built in 1979, twenty years after Wright’s death, from plans he drew–and living in one of his buildings is a continual balancing act. “All owners of Frank Lloyd Wright houses are plagued by curious people,” says Brink. On a recent visit to the house, while looking out a window with Mary Palmer, I saw a car slow down and creep along as it passed the house. Mary told me that happened all the time. As if anticipating this kind of attention, Wright designed the house for maximum privacy. Not much can be seen from the road, and what is in view tells very little about the delights inside and out back.

“She was the perfect client for Mr. Wright,” says Bruce Niethammer of Mary Palmer. Even after Wright’s death in 1959, the Palmers kept the house as close as possible to his original conception. At first Mary worked closely with John Howe and Larry Brink; Howe has since died, but Mary still works with Brink. For instance, Wright designed chairs for the living room, but the Palmers used some Scandinavian chairs instead. Mary was never satisfied with them, and turned to Brink for help. Using Wright’s original design, he figured out how to make Wright’s chairs and had them fabricated by Phipps of Port Huron.

And of course, it wouldn’t be a Frank Lloyd Wright house without a challenging roof–but again Brink, with Niethammer executing the plans, has devised improvements that keep the look of the house intact while keeping the Palmers dry. “Mr. Wright lived on the edge in his architecture,” explains Niethammer. “Low sloping roofs are not really suited for cedar shingles. It’s too shady–too flat. It’s pretty, but it holds moisture, because the water doesn’t run off.” Close attention to maintenance has saved the sloping roof, while the original tar sections of the flat roof have been replaced with lead-coated tin.

Palmer, still as enamored of Wright as ever, bristles at any criticisms, saying, “Everything you hear about Mr. Wright has two sides.” On my original visit she had me move from the couch to the Wright-designed chairs to show me how comfortable they were, and later she had me make the same test with the dining room chairs. She is appalled that people will say to her, “But do you really live here?”–or, worse, “I think it’s an interesting house, but I certainly wouldn’t want to live here.” She is unambiguously not in agreement: “I can’t imagine having something so fulfilling in so many ways–visually, the tremendous serenity, the fantastic drama.”

Beyond its own pleasures, the house has given the Palmers opportunities to meet fascinating people, many of whom ended up as friends. “Anyone interested in architecture comes to Mary’s,” says Brink. Bob Metcalf recalls a big Wright symposium in the 1970s attended by all the leading Wright scholars. In honor of the event, architecture students painted a 120-foot canvas of a building Wright designed but never built for a site in Kansas, and hung the canvas from Burton Tower. The event ended with a big party at the Palmers’ for all the participants. More recently a delegation of Japanese architects, led by Taliesin-trained Raco Indo, visited the house. E. Fay Jones, a Taliesin-trained architect best known for his Thorncrown Chapel in Arkansas, and the celebrated Indian architect Charles Correa, a U-M architecture graduate, have also visited.

“As a group, musicians seem to seek out the house as well as architects,” Mary says, remembering the time she got to hear Hephzibah Menuhin, Yehudi’s sister, play their grand piano. Menuhin was staying at Inglis House before a concert, and Gail Rector, then head of the University Musical Society, asked the Palmers whether Menuhin could practice on their piano. Menuhin came over and ran through her entire program. Asked if she listened, Mary replies, “Of course.”

More recently, the house gave her the opportunity to befriend members of the Royal Shakespeare Company, who gave awe-inspiring performances of Henry VI and Richard III under UMS auspices last March. Current UMS president Ken Fischer is a great friend and admirer of Mary Palmer, and when a group from RSC visited Ann Arbor a year before the performances to check out the facilities, Fischer took them to see the Palmers’ house. They raved about the experience, and when the whole troupe came the next year, another visit was high on their wish list. Mary responded by inviting all of the actors to tea–served on the “India Tree” Spode china that Wright had personally selected for the house.

Mary gained more than fond memories from the RSC visit. She actually acquired an addition to her house: a piece of “sculpture” for her garden. Tom Piper, an RSC set designer, had been among the first group to visit. When he returned the next year, Mary took him around the garden and said, winking, “Instead of charging, I ask advice. What’s missing is sculpture. I’ve been looking all my life, but nothing is right.” After discussing the question with the rest of the RSC group, Piper suggested they give her one of the ladders from the set.

Contacted by e-mail, Piper explains, “I wished there was a way to thank her for her hospitality and jokingly suggested that she should have the whole ‘hell mouth’ set in the garden. That seemed a little impractical!!! So I thought she should have one of the metal ladders as a memento of the play. Frank Lloyd Wright is a great hero of mine, and it’s wonderful to think of a bit of my set becoming a sculpture in the garden of one of his finest houses!”

The ladder, visible from the living room, is casually but artfully placed against a tree. As it rusts, it will fit even better into the ensemble of landscaping and house. It’s just the latest development in the continuing melding of Wright’s architecture with the Palmers’ interests and the greater community.

In retrospect, Mary Palmer says, “What attracted me to Mr. Wright was not pictures of the houses, not visiting other houses, but his philosophy that came into the house. It widened the whole reaction–how to live in the house, incorporating the landscape, the materials, the site–the whole big picture.”